In the light of the recent events concerning Aghoris,I’d like to share my personal experience in having dealt with them first hand over the last 6 years. I am slightly disturbed, even offended, by the picture of the Aghoris painted by a reputable media outlets. The recent news story has portrayed them as heinous men who, in the name of religion perform gruesome acts. In response to the backlash received from the Hindu community the news TV host quoted “ the Aghoris are an extreme Hindu sect” and “are not representative of Hinduism.” I disagree with this statement because all Aghoris have one thing in common-their devotion to lord Shiva, who is an integral part of Hindu Mythology. This being said it is not fair to disjoin aghoris from Hinduism. In fact, in the news story there was no mention of how these rituals originated, which if known, would explain their strange practices. What we see today is a result of there being an audience for such theatrics.

While most of the backlash to the new story is from Hindus defending their faith and wanting to have nothing to do with the abhorring Aghoris- the truth tends to get ignored.

The truth is that while there are true Aghoris, what you see on TV is far from reality. This impression does not encompass the true aghoris who have genuinely given up their lives in devotion. They are not necessarily all cannibals, they do not fling feces at each other nor do they wear or consume human remains; but some would for a price. They are mostly self-proclaimed saints,maybe runaways,mostly men who do not have any significant attachment to society.

Some follow the path of prayer, yoga and various spiritual practices. But sadly, there are men who take advantage of this publicity and assume the role of aghoris to capitalize on the recognition they are getting; which for them, would hopefully translate into monetary compensation.

The widely publicized grotesque representation of them is an act for some; they are not all on the path to attaining Nirvana, some are just men going to work- everything has a price; an ala-carte menu catered to your budget if you may.

While smearing ash on oneself is enough to play the part of alluring a tourist for a photograph, eating flesh will definitely have a price. While the media gets roaring ratings on the coverage of the absurd factor, the (wannabe)Aghoris get the incentive to act outrageously, as if continuously putting on a show. Sadly, since the false reality has already been created, there is a need to top the last absurd episode. Historically the true aspect of life for Aghoris is to avoid reincarnation. They believe in detachment from all things, they try their best to not get identified with the world. However the Aghoris we see depicted by the media clearly are very attached to the ungodly things like fame and money.

The existence of audience for such theatrics has resulted in the creation of any average Joe becoming an Aghori in the hopes of making a buck. What we end up with is a group of unholy men who capitalize on people's blind faith in the name of religion.

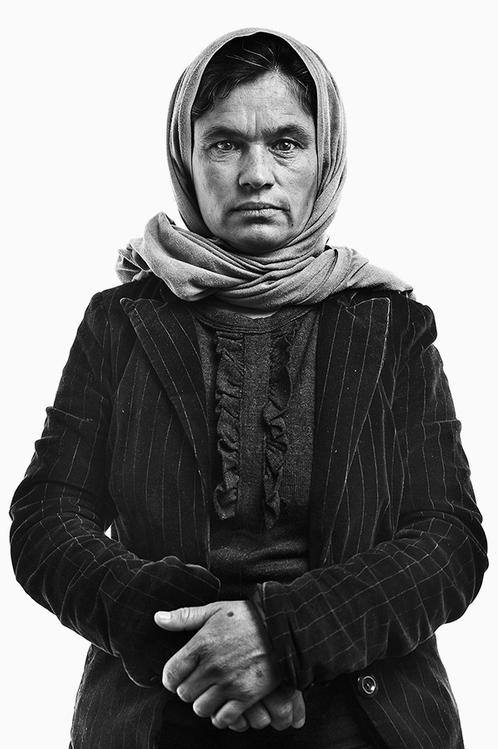

With this body of work I wish to break the common conception of Aghoris.

The Aghoris seem timeless,they appear to be so far removed from reality as we know it that the effects of time on them are hard to tell.

I had my first encounter with them in 2011 in Junaghad, Gujarat. It was the festival of Shivratri, the most mythologically important festival for the devotees of Lord Shiva. It is believed that a devotee who performs sincere worship of Lord Shiva on the auspicious day of Shivratri is absolved of sins and attains moksha.

The Aghoris have the same goal- to get freedom from the cycle of reincarnation.

They're almost ostracized because of their affinity towards death and other things we generally dislike. But they're energy often leads them to be revered as holy men having known to have healing powers and black magic powers.

Since I had a preconceived notion of the Aghoris, approaching them to ask if i could photograph them seemed like a rather daunting task. Maybe it was my nervousness and high level of discomfort but they seemed very guarded and wary of me. Looking them into the eye was difficult, I barely got 10 good shots.

Six years later, it was the same festival, same place and the same Aghoris, but I had changed. This time around, no one turned me down. Every Aghori baba I asked agreed to get his photo taken.They seemed less abominable, less scary, most of them beckoning me to them, many eager to stand in front of the camera for something in return. The more I looked around, the more apparent it got- they were mere mortals! Not every single one of them had divine powers, some were men just going to work- this being a way to sustain themselves.

It happened very quick, like shattering glass: when their halo lifted; the way they went from being holy divine men to just people that are different than us.

The Aghoris appear to be untouched by the constant evolution of society while the rest of us are trying so hard to keep with change. But once the veil of ignorance lifts, it's easy to tell apart hoaxes from those with honest intentions. This realization was jarring; it shakes one’s faith in..having faith. But it does the more important task of making one more aware, more present.

"I posses everything- all so fake

Hence I have nothing - to put at stake

I'll tell you a secret- and he'll it's true

I am the Aghori, dwelling deep in You."