The assignment seemed straightforward. As a part of the United Nations’ Development Program, I was to go to Iraq and take portraits of refugees. I knew it would be somewhat heavy considering the emotional weight behind the purpose of the shoot. But like many international projects, my focus was on my equipment, visas, logistics and mental planning of what I would hope to capture.

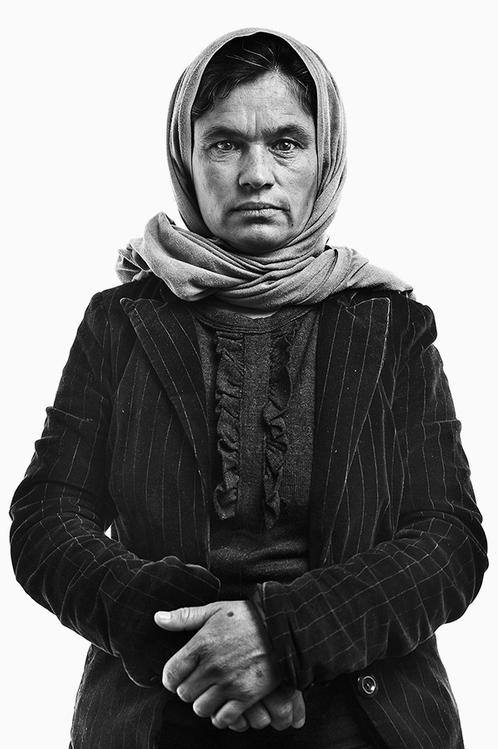

When we got to the Sharia Camp in Dohuk, my mind was still very much on the technical, even given the state of the tent camp, the somberness of it all. The camp houses 18,000 refugees in 4000 tents. I set up my backdrop. As I handled the large screen, I was introduced to the first person I was to photograph. The woman was stoic, hardened, but calm.

I asked some introductory questions to the translator to get some of her story. He nodded, and then spoke to her. Her voice was softer than I would have imagined. Then the translator told me her words, “They would beat me every single day. And treated us like animals.” My attention now pulled away from my camera. I asked a few more questions to the translator.

He relayed to me that not only had she been beaten, she had been raped repeatedly. The ISIS rebels had used heavy weapons to subdue her and her helpless family. They forced her children to learn Sharia Law. “They took my husband and my children away. Please help me find them.”

I had a painful realization. This woman in front of me, all her freedoms removed by gun point, had suffered one-only-knows how many months of being of ordered and controlled, brutalized and beaten by men with their own agendas. I am a man with a camera, used to directing people to bend and shift for my lens. I too had an agenda. My heart was crushed. I couldn’t dare be another man giving her orders. From that moment there was a total shift in me. The delicacy and humanity of what I was there for seeped through all of the travel jitters and goals. A greater sense of responsibility filled me. These people were not only in need of a voice, but as the one carrying that voice to the other side, I was going to have to do so with great tenderness, a kind of tenderness that up until that point I had not ever yielded with my subjects.

I took a deep breath. I was probably only going to be able to take one photo. Anything more than one would have been an injustice to her in that moment. I told the translator. “I just need her to face me.” I smiled at her kindly, as peacefully as possible, to assure her even a minute amount of comfort. I held my breath as I snapped and let it out as I checked the view screen. One shot. I thanked her and she walked away.